Key points

Sometimes, no matter how hard you try to fall asleep, sleep will not come. We’ve all been there. You find yourself thinking: “Will I ever fall asleep? Why can’t I sleep? How long do I have left in bed? I’m going to be exhausted tomorrow…”

This is a what we call a self-fulfilling prophecy. When this happens night after night, you can find yourself trapped in a cycle of worry and poor sleep. Luckily, this article’s going to show you how to break this cycle. We’ll cover:

- why worrying can be a healthy and normal response to deal with stress and avoid danger

- the difference between healthy worrying and self-fulfilling prophecies

- how anticipating that you won’t sleep can lead to not sleeping

- the simple yet powerful technique of paradoxical intention

- further steps you can take if you need more help to overcome negative thoughts and take back control of your sleep.

Are your worries keeping you awake?

If negative thoughts keep crowding your mind and keeping you up at night, you can find yourself running on fumes. It’s easy to get into an endless cycle of worrying about sleep and then finding yourself unable to. But we can help. Our course equips you with the tools and knowledge you need to banish negative thought patterns and get back to enjoying your days, fuelled by worry-free, refreshing sleep.

It’s easy to worry when you just can’t fall asleep

It can be really difficult to fall asleep if you’re getting into bed and already worrying that you’ll be stuck awake all night. It’s a problem that many of us will experience. You lie awake, letting your worries about why you can’t sleep multiply in your head.

Then, when you finally drift off, you don’t end up getting the quantity or quality of sleep you need to function at your best the next day. You wake up exhausted and tell yourself you were right to be worried. You thought you wouldn’t sleep, and you didn’t.

You’ve just experienced a self-fulfilling prophecy. When this kind of worry repeats night after night, you can find yourself in a cycle where poor sleep feeds the negative thoughts and the negative thinking ruins your sleep.

Thankfully, you can break this cycle with some simple adjustments to how you’re thinking. In this article we’re going to show you how to do this and explain how tweaking your nightly routine can also help you to relax and keep worries at bay.

We’ll help you better understand how worrying about falling asleep can come between you and a good night’s sleep. We’ll also show you some simple approaches that can calm your body and mind and stop negative thoughts from interfering with your sleep.

Let’s get started by looking at how it’s natural for you to worry sometimes and how to identify when a negative worry cycle is getting in the way of your sleep.

Worry can be a healthy and helpful response to life’s challenges

It’s totally normal to worry about things like your health, financial affairs and your loved ones. Often, this worry is useful and allows us to plan and prepare for the unexpected. If you can identify something that’s worrying you, you can take steps to reduce risks. For example:

- you’re concerned about your health, so you make a plan to start walking more

- your finances are stressing you out, so you decide to create a budget

- you worry about a friend who’s been down recently, so you phone them for a catch up.

These are just simple examples, but they illustrate a healthy pattern where you worry about something and then try to solve it. This process reduces your worry level and you move on.

But there’s another scenario that can arise instead where your thoughts spiral until you’re picturing the worst thing that could happen. Let’s take the first example from above:

- you worry about your health… Maybe you’re going to get sick. Maybe it’s something serious. What if you can’t work? How will you pay the bills?

And it goes on and on, as you fall down a rabbit hole of negative thinking.

Once you’re doing this, it becomes easy to look as hard as you can for signs that the worst thing that can happen will happen.

Picture this: a waitress who’s got a talent for never dropping dishes.

- The waitress’s manager praises her because she’s never dropped a single dish.

- She then becomes conscious about the way she walks between the kitchen and the tables she’s waiting on — she wants to maintain her good reputation.

- Over time, she worries more and more about every step and minor loss of balance. Before she was praised this never crossed her mind!

- Because she’s concentrating on her worries and not the dishes, she makes more missteps and one day drops a pile of dishes.1

She’d never dropped a plate until she started worrying about it happening, and so she ends up dropping one. So how does this apply to sleep problems?

This is a good question. After all, if you’re reading this you’re probably not looking for lessons in balancing dishes. You want to get better sleep.

The process of going off to sleep isn’t immune to this kind of negative thinking. It’s very common for people living with sleep difficulties such as insomnia to have performance anxieties linked to how well they’re going to sleep.2

This anxiety is totally understandable but causes more problems than it solves. Let’s look at this in a bit more detail now.

Negative thinking can lead to psychological arousal

One way worry causes difficulty sleeping is because it keeps your mind active at bedtime. We call this psychological arousal and it’s the opposite of how your mind should be when you’re trying to go to sleep.

Psychological arousal plays a huge part in keeping us awake. For instance:

- you go to bed convinced you’re going to have an awful night’s sleep

- you lie in bed, getting irritated that you can’t fall asleep

- you start to get even more annoyed (i.e. psychologically aroused) about the fact you’re still awake.

The increased anxiety makes it even more difficult to fall asleep and you can find yourself lying wide awake, frustrated or angry that you’re just not sleeping. What’s even more infuriating is that it all stemmed from the initial thought that a bad night’s sleep was inevitable!

Poor sleep can increase feelings of negativity

It’s well-established that sleep and mental health are interlinked. Good sleep can boost your mental health and not getting enough sleep can affect your emotional wellbeing. Feelings of stress, anxiety and depression can increase with poor sleep, and these can in turn make it harder for you to sleep.

Plus, not getting enough sleep can make you experience negative feelings more intensely. So your negative thoughts at bedtime stop you getting the sleep you need and the next day you may notice your mood is lower. Life looks a little bleaker because you didn’t get enough sleep.

This just feeds into the cycle of negative thinking and poor sleep. This all sounds very depressing and you might be thinking at this point that everything looks hopeless. It’s absolutely not and there’re plenty of straightforward ways to break this cycle.

We’ve identified that there’s a problem with how your thoughts are sabotaging your sleep. It’s now time to put a stop to all this negativity. Let’s focus now on how to fix it.

Simple steps to keep negative thoughts at bay

We’ll start with some simple techniques and tips that often get overlooked.

Write a to do list

Your negative thoughts at bedtime might not just be centred around your sleep. You could be getting into bed and negative thoughts around your daily life start to intrude.

Work strifes may be playing on your mind, you may realise you needed to do things around the house but forgot, maybe you’re focusing on a disagreement you had with someone… These thoughts have no place in your bedtime, so you need them out of your head.

A simple way that can help is to make a list. Before you go to bed, take a moment to think about your day and write down the things that are unresolved or need to be addressed tomorrow.

This can help to clear your mind when you get into bed. If these type of negative thoughts creep in as you’re trying to sleep, you can also keep a pen and paper close by and jot them down.

Resist the urge to look at your devices

Keep your screens out of your bedroom and try not to turn to them if you’re not managing to fall asleep. The light from their screens can interfere with production of melatonin, a key hormone responsible for making you feel sleepy.

The content of what you’re looking at could also contribute to keeping you awake. Watching something on your favourite streaming site or scrolling through your social media feed might feel relaxing, but the content might end up keeping you awake.

For example, a high-intensity series on Netflix or a social media post that makes you angry or excited can keep your brain in an aroused state. When you’re preparing for sleep, you want your mind to relax, not stay alert.

We’ve already talked about how worry keeps your brain alert when you’re trying to get to sleep. With this in mind, you should aim to limit other activities that can add to this state of psychological arousal and opt for activities that help you relax instead.

It’s worth including wearable sleep trackers here too. Devices that track your sleep can offer insights into how you’ve slept but their scope is limited and this can end up causing further worry. While wearable sleep trackers may identify trends in your sleep, the technology isn’t perfect.

If you’re already worrying about your sleep and then your tracker tells you that you’ve slept badly, it can heighten your anxiety about your sleep. For example, if you wake up and feel refreshed, but your tracker says you slept badly, what do you trust?

The answer should be that you trust how you feel, but for some people they become reliant on the information from their tracker and this can create additional anxiety around their sleep.

Dedicate some time to winding down before sleep

Creating a simple wind-down routine to follow before you go to bed can be an excellent way to destress before bed. Spending a little time on relaxing and calming activities before bed can help your body and mind prepare for sleep.

A nice warm bath or some time spent reading a book can be enough to reduce stress and clear your mind before bed. It doesn’t matter what activity you choose, as long as you personally find it to be relaxing.

Make your bedroom a positive sleep space

If walking into your bedroom makes you furrow your brow because it’s messy/uninviting/too hot/too cold/too noisy or anything in between, then you’re going to go to bed with negative thoughts already on your mind.

You want your room to be relaxing and inviting. Somewhere you look forward to escaping to after a long day. Think about your ideal bedroom setup and consider making simple changes to help your sleep space be a positive place.

All of these suggestions can help to make you feel relaxed and less stressed when you go to bed. This in turn may help you to feel less negative when trying to sleep.

Let’s move on to specifically addressing your negative thoughts with a technique to help you banish your worries and get back to sleeping soundly.

Paradoxical intention can help break the cycle of negative thoughts

One way to address a self-fulfilling prophecy is through an approach called paradoxical intention. This might sound complex and maybe a little daunting, but it’s really quite simple. Let’s break it down:

- a paradox is something that seems like the opposite of common sense, but is actually true

- your intention is something you want to do or plan to do.

So we can say that paradoxical intention involves doing something that seems to go against common sense.

The techniques behind paradoxical intention were first developed to help people cope with stress and anxiety. Since then, this approach has been found to be an effective way to deal with unhelpful, self-fulfilling prophecies around sleep.3

The theory behind this is that when you’re stressed about your sleep, actively trying to get to sleep can interfere with you getting to sleep.

What exactly is stressing you out about sleep is unique to you but might involve:

- fear that taking a long time to drift off means that you won’t ever fall asleep

- annoyance at the fact that you can’t sleep

- fear that a lack of sleep will affect you the following day e.g. through poor concentration4

- worry that poor sleep will lead to you developing serious medical conditions.5

In studies where participants were instructed to fall asleep as quickly as possible, while being exposed to something stressful (listening to lively music or trying to win a prize for falling asleep) they either took longer to fall asleep or experienced more fragmented sleep.6 7

So if you can somehow remove the stress, then it’s possible to turn the issue on its head and break self-fulfilling, fearful thoughts about sleep.

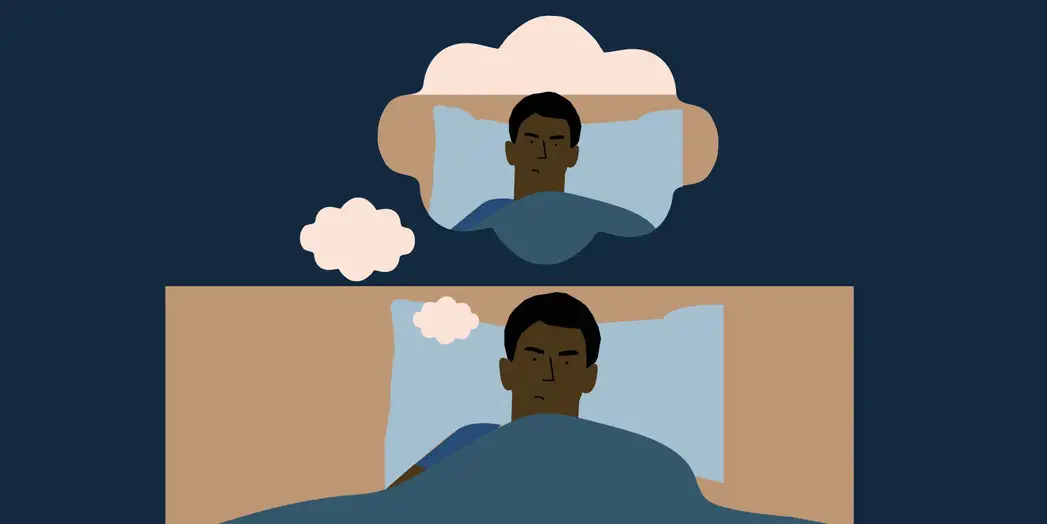

Using paradoxical intention to fall asleep faster

How do you do this? Like we mentioned earlier, the solution might sound a bit illogical, but bear with us. If you want to fall asleep, you need to do the opposite: try not to fall asleep!

When worrying too much about going to sleep costs you sleep time, then the opposite should apply: thinking about, and trying to, stay awake should help you to fall asleep.

You need to challenge yourself to stay awake. To do this, you can try any or all of the steps below.

- Simply try lying in bed in the dark (ideally after having followed your wind-down routine), either with your eyes open or closed.8 9

- Avoid anything active when attempting to stay awake before or during this time. Steer clear of drinking a huge coffee before bed or doing things like reading or checking your phone once in bed.

- Lie still and stay awake for as long as possible, gently resisting sleep.

- Congratulate yourself for staying awake, even if you’re starting to feel sleepy.

- Reassure yourself that it’s fine to stay awake this long. Remember that it’s OK — it’s the purpose of the practice. You’re doing well.10

By following these steps over a number of nights, you may feel that you fall asleep faster and that your sleep is less fragmented. You might also find that the worries you have about your sleep don’t seem quite as bad as they once were.11

Even though this technique might seem overly simple (and a little contradictory) it has been shown to be very effective at reducing anxiety about going to sleep.

Studies have shown that it can reduce how long it takes you to get to sleep, can help you to stay awake during the night and can improve how rested you feel when you wake up.12 So paradoxical intentions really can have some pretty impressive benefits!

Paradoxical intention has some limitations

While this technique can work for people who have difficulty getting to sleep because of negative thoughts, it won’t work for everyone with a sleep problem. Sometimes, it’s more effective to try other techniques to help you sleep.

These can include stimulus control,8 thought blocking or sleep restriction as part of an integrated, tailored treatment plan.

If you’re finding that paradoxical intention isn’t really helping, it might be that you need further support. With the help of your dedicated sleep coaches, who are in turn supported by our sleep experts, therapists and clinicians, you’ll be able to understand what’s impacting your sleep and the changes you need to make to start sleeping peacefully again.

And this is where our fully supported digital sleep programme excels.

We review your sleep individually and discuss your sleep problem with you. We then use this to build you a fully-personalised sleep plan to meet your specific needs. You’ll have sleep coaches on hand to help and support you at every step of the way.

Our techniques have been clinically validated and our programme is highly effective. Whether you think your sleep problems are mild, recent, deep-rooted or severe, we can help.

We’ve helped thousand of people just like you find the sleep they need, so why not let us guide you back to sleeping well? Sign up to our digital sleep clinic is simple, answer a few short questions about your sleep and you’ll be back to sleeping soundly in no time at all.

Summary

Worrying can be a normal and healthy response to the stresses and strains of everyday life. But repeated worrying can lead to developing negative beliefs around sleep.

- Constantly thinking about all the ways in which things could go wrong can create an unhealthy cycle of worrying.

- Putting too much pressure on your body to sleep well creates performance anxiety and can keep you awake.

- Trying to stay awake when you want to sleep is an approach called paradoxical intention.

- While it might sound a bit illogical, this technique can really help you challenge negative thoughts and fall asleep quicker.

- Using paradoxical intention alongside good sleep habits can help put you in a more sleep-friendly state and make it easier to fall asleep.

References

- Ascher LM. Paradoxical Intention and Related Techniques. In: Encyclopedia of Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Springer-Verlag: New York, 2006, pp 264–268. ↩︎

- Lundh L-G, Lundqvist K, Broman J-E, Hetta J. Vicious cycles of sleeplessness, sleep phobia, and sleep-incompatible behaviours in patients with persistent insomnia. Scand J Behav Ther 1991; 20: 101–114. ↩︎

- Wegner DM. How to think, say, or do precisely the worst thing for any occasion. Science 2009; 325: 48–50. ↩︎

- Ascher LM, Efran JS. Use of paradoxical intention in a behavioral program for sleep onset insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978; 46: 547–550.

↩︎ - Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep 2017; 9: 151–161. ↩︎

- Ansfield ME, Wegner DM, Bowser R. Ironic effects of sleep urgency. Behav Res Ther 1996; 34: 523–531.

↩︎ - Rasskazova E, Zavalko I, Tkhostov A, Dorohov V. High intention to fall asleep causes sleep fragmentation. J Sleep Res 2014; 23: 295–301. ↩︎

- Baillargeon L, Demers M, Ladouceur R. Stimulus-control: nonpharmacologic treatment for insomnia. Can Fam Physician 1998; 44: 73–79. ↩︎

- Relinger H, Bornstein PH. Treatment of Sleep Onset Insomnia by Paradoxical Instruction: A Multiple Baseline Design. Behavior Modification 1979; 3: 203–222. ↩︎

- Michael J, Sateia D. Insomnia: Diagnosis and treatment. 1st Edition. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2016 doi:10.3109/9781420080803. ↩︎

- Broomfield NM, Espie CA. Initial insomnia and paradoxical intention: An experimental investigation of putative mechanisms using subjective and actigraphic measurement of sleep. Behav Cogn Psychother 2003; 31: 313–324. ↩︎

- Jansson-Fröjmark M, Alfonsson S, Bohman B, Rozental A, Norell-Clarke A. Paradoxical intention for insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res 2022; 31: e13464. ↩︎