Key points

You’ve no doubt heard of REM sleep but what does it actually mean and why’s it important to you? In this article we’re going to explore:

- exactly what we mean by REM sleep

- why REM sleep is so important

- what you can do to improve your REM sleep

- what to do if you’re experiencing a sleep problem.

REM makes up around 25% of your sleep

When you fall asleep, it may feel like the body goes into a kind of standby mode. The brain powers down, plays some movies in the form of dreams and then, before you know it, the whole system powers back up in the morning.

But this is far from what’s actually happening. In reality, your brain remains active during sleep and your sleep itself is very structured. Sleep occurs in stages defined by what’s happening to your brainwaves.

There are four sleep stages and you cycle through them several times a night. Stages 1-3 are called non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and stage 4, the one we’re going to focus on in this article, is rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Each sleep cycle lasts somewhere between 90-120 minutes and the cycles lengthen throughout the night. With each sleep cycle, the amount of time you spend in REM increases, so the latter half of the night is when you should be getting most of your REM sleep.

We know that various processes are occurring in your body and brain during the different stages of your sleep. In this article we’re going to explore what’s going on in your body during REM sleep and why it’s important to ensure you’re getting enough of this sleep stage.

Are you getting enough REM sleep?

If you’re waking up after a full night of sleep feeling groggy and finding it hard to concentrate during the day then you might not be getting enough REM sleep. If this sounds like you, take our short sleep quiz to see how our sleep improvement plan can help you back to healthy, balanced sleep.

What is REM?

Rapid eye movement: the clue’s in the name here. At its most basic level, REM sleep is a phase of sleep where the eyes move frequently and rapidly under the eyelids. It got its name after researchers noted that babies have periods of active sleep, where these rapid eye movements were seen, followed by periods of calm sleep.1

Later studies showed that specific patterns of brainwaves occur during REM sleep2 and we experience long, narrative dreams during this sleep stage.3 We now also know that brain activity during REM sleep is similar to that seen when we’re awake.

Your heart rate and blood pressure also increase to levels similar to when you’re awake and breathing becomes faster and irregular. Apart from small muscle twitches the body loses all muscle tone,4 essentially becoming temporarily paralysed, which may be to stop us acting out our dreams.

So we can sum up REM as a period of our sleep where our body barely moves, our brain is active and we’re highly likely to be dreaming. What this doesn’t tell us is why we experience this sleep stage and so we’ll explore that next.

What’s the purpose of REM sleep?

We don’t know with 100% certainty the exact reasons for this unique sleep stage. Many theories have been put forward and the fact that we experience most of our dreams during REM may be important.

One hypothesis is that REM sleep is important for brain development. As we’ve mentioned earlier, REM sleep was first identified in babies, and we now know that newborn mammals (including humans) spend most of their early lives in REM sleep.5

As humans develop and mature, the amount of REM sleep gets less and less and eventually levels out in early adulthood.6 Levels remain consistent until later adulthood, when sleep can become more fragmented and REM sleep levels reduce.7 8

REM is also thought to be a stage of sleep that’s key for certain types of memories being formed and consolidated.5 It’s thought that emotions and emotional memories are processed during REM9 as well as memories related to motor learning (movement).10

This is known as memory consolidation and occurs in both deep sleep and REM.

Deep sleep is what we call the third stage of NREM sleep and it occurs just before REM sleep. It’s thought that the two stages together are crucial for this process and that each is important for consolidation of certain types of memory.

You can think of memory consolidation as a bit like scrolling through the videos and photos on your phone.

We keep the images that mean something to us but delete the ones that have a thumb over the lens or show something we needed in the moment, that’s no longer useful. We can organise the ones we keep into folders, by date, content, colour… Whatever we choose.

Though the actual mechanisms involved are far more complex, this is a good way to think of memory consolidation.

REM sleep may also facilitate learning.10 There’s an interesting study that suggests that during REM sleep the brain sorts and filters connections that have been made in the brain during the day. It keeps connections that are useful or important and cuts those that we don’t need to keep.

Just imagine a fruit tree that’s grown lots of new branches. Although the growth is good and shows the tree’s healthy, not all the branches are needed or helpful for the tree to bear fruit.

So we prune off the extra branches — the ones that are in bad condition and the ones that are deadwood. This is a little like what may be happening during REM sleep to the connections that have been made in the brain during the day.

REM sleep may be important for strengthening and maintaining synapses (the branches) in the brain (the tree).10 It’s thought that memories and processes involved in motor learning are processed during REM in this way.

So, while these functions are still not fully understood, it seems likely that REM sleep is key for certain areas related to memory, learning and development.

REM sleep vs deep sleep

REM sleep and deep sleep are often confused with each other but there’re distinct differences between the two. Someone in REM sleep may be hard to wake up, which is why this stage is often classed as being deep sleep.

But as we’ve already discussed, during REM your brain activity is similar to when you’re awake, which doesn’t quite fit with being ‘deep sleep’. When we talk about true ‘deep sleep’ we’re referring to the third sleep stage, often called N3 or slow-wave sleep.

During your first few sleep cycles, N3 is the final NREM sleep stage that occurs just before REM. As your sleep cycles continue throughout the night, N3 sleep no longer occurs and you enter lighter N2 sleep before REM instead.

What this means is that you experience your deepest sleep during the first half of the night, while the latter half of the night your sleep is slightly lighter.

We know that memories are processed in deep sleep and REM and it’s thought that both stages together are important for memory consolidation. The difference between REM and deep sleep can be explained by what’s happening in the body and mind during these two sleep stages.

Deep sleep is considered to be when your mind and body rest and recover from whatever the day has thrown at you. Muscles and tissues are repaired, the immune system is strengthened and this sleep stage is thought to be key to you waking up feeling refreshed the next day.

During deep sleep, you’re in a really relaxed state and your breathing and pulse rates slow down. Brain waves follow a distinct pattern during deep sleep, which is why it’s also referred to as slow-wave sleep.

This is very different to what’s going on in REM sleep. As we talked about in the last section, in REM your breathing and pulse rates increase and brain activity is similar to that seen when you’re awake.

So it’s clear that deep sleep and REM both have important roles that sometimes overlap. But when it comes to deciding which stage of sleep is actually the deepest, things can get a little foggy.

How much REM sleep do you need?

We’ve already mentioned that our sleep is organised into cycles. In the first cycle, the time spent in REM sleep is usually quite short, lasting as little as 1-5 minutes.11 With each further sleep cycle, the time we spend in REM increases and the final cycle of REM before you wake up can last for up to an hour.12

There’s no set figure for how long you should spend in REM each night. It can vary on a day-to-day basis and will depend on factors such as your age and lifestyle. It’s generally accepted that REM sleep makes up somewhere between 20-25% of our sleep when we’re sleeping well.

So if you can’t put an actual number on how much REM sleep you need, how do you tell if you’re getting enough?

If you’re getting enough quality sleep overall, then your brain will take care of the rest to ensure you’re getting all the REM sleep you need.

If you’re waking up feeling refreshed, both mentally and physically, with the energy you need to get through your day, then you can consider that your overall sleep is adequate and so you’re getting enough REM.

Why is REM sleep important?

As we’ve talked about in the last section, REM sleep is thought to be the time when we process emotions that we’ve experienced during the day and it’s the stage of sleep in which we consolidate these emotional memories.

Scientific studies have shown that lack of REM sleep reduces the formation of emotional memories.5 It’s also known that changes to REM sleep are seen in mental health disorders such as major depression, bipolar disorder and post traumatic stress disorder.9

These changes can involve how long the person spends in REM, when they go into REM stage or how many periods of REM they experience during the night.

When our REM sleep is compromised, how we feel emotionally when we’re awake and how we make emotional memories during sleep can both be affected.

It’s also been shown that when REM sleep is impaired, we can find it harder to learn things. Studies have shown that when participants are asked to learn something, then deprived of REM sleep, they struggle to recount what they learned the previous day.

As REM is thought to be important for mood, learning and memory formation, it stands to reason that lack of REM would have a negative impact on these too.

However, this might not necessarily always be the case. In other studies scientists have looked at the effect of depriving people of REM sleep. Results showed that, at least for periods of up to two weeks, the loss of REM sleep doesn’t have a noticeable effect on behaviour.13

Similarly, certain medications used to treat depression may lead to reduction or loss of REM sleep phase for the person taking them. Yet the person doesn’t experience negative effects as a result, even when the drug is taken for several years.13

Do animals have REM sleep?

Yes! A lot of what we know about REM sleep is actually from studies in animals. We know that most mammals and birds experience REM sleep. In fact, some of the earliest studies of REM were in animals ― not long after REM was identified in babies, it was also identified in cats.14

If you’ve ever seen your pet dog or cat twitching in their sleep, then it’s highly likely that they’re in REM sleep.

Different species vary in how much REM they have and how it’s distributed during their sleep. For example, elephants have very little REM sleep and can go for days without it, whereas cats spend about eight hours a day in REM.5

Sleep disorders and REM sleep

REM sleep has been shown to be altered in several sleep disorders, including:

- obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

- narcolepsy, both with and without cataplexy

- sleep paralysis

- REM sleep behaviour disorder.

In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) the airway collapses, causing breathing to stop and start during the night. Sleep apnea can occur in NREM or REM but can be more pronounced during REM sleep. This is thought to be down to the reduced muscle tone that occurs during REM sleep.

There’s also a sub-group of OSA called REM-related OSA, in which the person’s apnea is mostly confined to their periods of REM sleep.15 This type is thought to account for somewhere between 10-36% of all OSAs.16

Narcolepsy is another sleep disorder that is associated with REM sleep. In narcolepsy, those affected experience daytime drowsiness and periods where they suddenly fall asleep. Their REM sleep is disturbed and can occur as soon as sleep onset begins, or may even begin when the person is awake.17

As we know that REM sleep involves temporary paralysis of the muscles, when people experience this with narcolepsy, it can appear like they’re fainting. The person with narcolepsy can drop to the floor in a state of REM sleep. This sudden loss of muscle tone is known as cataplexy.

Sleep paralysis can also occur with narcolepsy or can also be an independent sleep disorder itself. Sleep paralysis is a normal part of REM sleep but when it occurs outside of REM sleep, it’s considered to be a disorder.

Someone experiencing sleep paralysis will be aware of their surroundings but unable to move, and this can obviously be very frightening.

REM sleep behaviour disorder

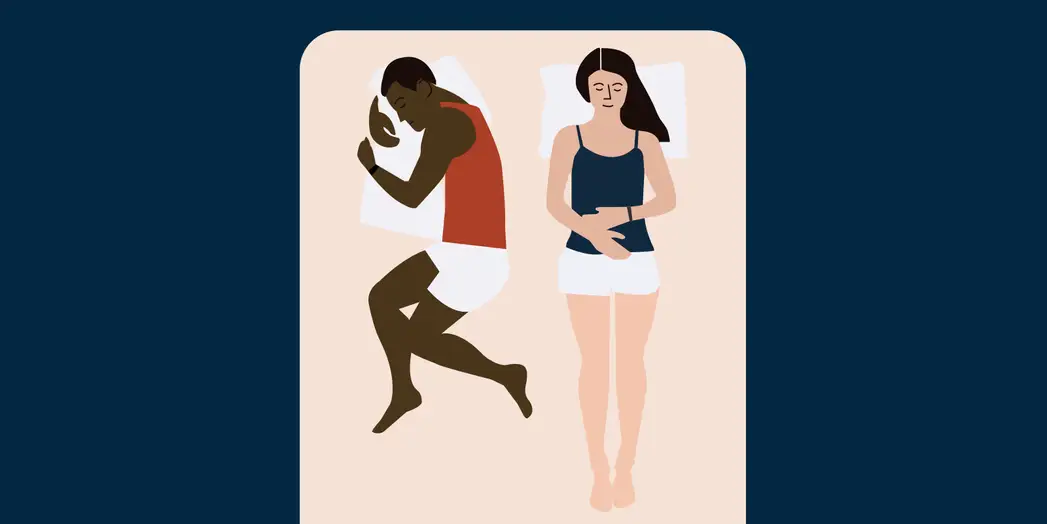

REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) is almost like a reverse of sleep paralysis, in that the person experiencing it is very much in REM sleep, but their muscle movements aren’t restricted.

This means that someone who is dreaming about playing football (for example) could actually be carrying out the physical movements associated with kicking a ball, shouting to the ref or tackling an opponent while they’re asleep, in bed.

There’s a risk of injury to the person experiencing REM sleep disorder and also to their bed partner, so it’s a disorder that can cause significant disruption to both your sleep and your daily life.

From this short list, it’s clear that disruption to REM sleep architecture can have dramatic effects on your sleep and in the case of OSA, REM sleep itself can worsen symptoms. So as with any sleep disorder, treatment is key.

How can I make sure I’m getting enough REM sleep?

To take care of your REM sleep, you need to take care of your sleep as a whole.

There are several things that can interfere with either the amount or timing of REM sleep, including alcohol, coffee nicotine or certain medication (including some medication for sleep).

If you’re experiencing trouble sleeping then you could consider reducing your alcohol or caffeine intake to see if that helps. Taking some simple steps to improve your overall sleep is also a good idea.

Simple steps you can take to improve your sleep can include setting up a wind-down routine that you can follow each evening, reducing screen time before bed and ensuring your bedroom is a calm and inviting place in which to sleep.

Can you have too much REM sleep? It seems so. It’s known that stress and anxiety can lead to increased time spent in REM and can alter when we go into REM and how long we spend in this stage.18 Too much REM can leave you feeling tired and groggy the next day.

So if you’re experiencing stress or anxiety, you may also be unknowingly experiencing alterations to your REM sleep. Taking steps to improve your mental health can have a direct impact on your sleep and, likewise, improving your sleep can improve your mental health.

When you sleep well, you’ll benefit from a natural balance between all of the sleep stages. So remember, if you’re taking good care of your sleep, then your REM will take care of itself.

Summary

- REM sleep is thought to be important for mood, memories and learning.

- During REM, brain activity is similar to that seen when we’re awake.

- Not getting enough REM sleep can affect our mood, memory and ability to learn.

- If you’re experiencing a sleep problem, your REM sleep may be affected.

- To take care of your REM sleep, you need to take care of your sleep as a whole.

References

- Aserinsky E, Kleitman N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Science 1953; 118: 273–274. ↩︎

- Dement W, Kleitman N. Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility, and dreaming. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1957; 9: 673–690. ↩︎

- Dement W, Kleitman N. The relation of eye movements during sleep to dream activity: an objective method for the study of dreaming. J Exp Psychol 1957; 53: 339–346. ↩︎

- Siegel JM. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. W.B. Saunders Company, 2005. ↩︎

- Peever J, Fuller PM. The biology of REM sleep. Curr Biol 2017; 27: R1237–R1248. ↩︎

- Bathory E, Tomopoulos S. Sleep regulation, physiology and development, sleep duration and patterns, and sleep hygiene in infants, toddlers, and preschool-age children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2017 Feb;47(2): 29–42. ↩︎

- Van Cauter E, Leproult R, Plat L. Age-related changes in slow wave sleep and REM sleep and relationship with growth hormone and cortisol levels in healthy men. JAMA 2000; 284: 861–868. ↩︎

- Jiang F. Sleep and early brain development. Ann Nutr Metab 2019; 75 Suppl 1: 44–54. ↩︎

- Glosemeyer RW, Diekelmann S, Cassel W, Kesper K, Koehler U, Westermann S et al. Selective suppression of rapid eye movement sleep increases next-day negative affect and amygdala responses to social exclusion. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 17325. ↩︎

- Li W, Ma L, Yang G, Gan W-B. REM sleep selectively prunes and maintains new synapses in development and learning. Nat Neurosci 2017; 20: 427–437. ↩︎

- Colten HR, Altevogt BM, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. Sleep physiology. National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., DC, USA, 2006. ↩︎

- Patel AK, Reddy V, Araujo JF. Physiology, Sleep Stages. StatPearls Publishing, 2021. ↩︎

- Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Katz LC, LaMantia A-S, McNamara JO et al. The possible functions of REM sleep and dreaming. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2001. ↩︎

- Jouvet M, Michel F. Electromyographic correlations of sleep in the chronic decorticate & mesencephalic cat. Comptes rendus des seances de la Societe de biologie et de ses filiales. 1959;153(3):422-5. ↩︎

- Djonlagic I, Guo M, Igue M, Malhotra A, Stickgold R. REM-related obstructive sleep apnea: when does it matter? Effect on motor memory consolidation versus emotional health. J Clin Sleep Med 2020; 16: 377–384. ↩︎

- Aurora RN, Crainiceanu C, Gottlieb DJ, Kim JS, Punjabi NM. Obstructive sleep apnea during REM sleep and cardiovascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: 653–660. ↩︎

- Nishino S, Riehl J, Hong J, Kwan M, Reid M, Mignot E. Is narcolepsy a REM sleep disorder? Analysis of sleep abnormalities in narcoleptic Dobermans. Neurosci Res 2000; 38: 437–446. ↩︎

- Staner L. Sleep and anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2003; 5: 249–258. ↩︎